When the pandemic first hit, a number of enterprising performing arts venues used virtual programming to reach audiences in lockdown. But with the return of in-person shows, many theaters in the UK are canceling their virtual offerings.

According to Digital Access to Arts and Culture Beyond COVID-19, a 12-month research project developed by the UK’s Arts and Humanities Research Council, a mere 60 out of 224 UK theaters are offering livestreamed performances this Fall, whether due to budgetary constraints, lack of digital strategies, or other complications. Led by University of Kent’s Dr. Richard Misek and Loughborough University’s Dr. Adrian Leguina, the project aims to provide performing arts organizations with practical knowledge concerning digital programming.

“We’re doing analytics to get top-level findings around how many people are attending performances, how much money organizations are making from performances, and how many new audiences are attending compared to pre-existing audiences,” Misek tells Jing Culture & Commerce.

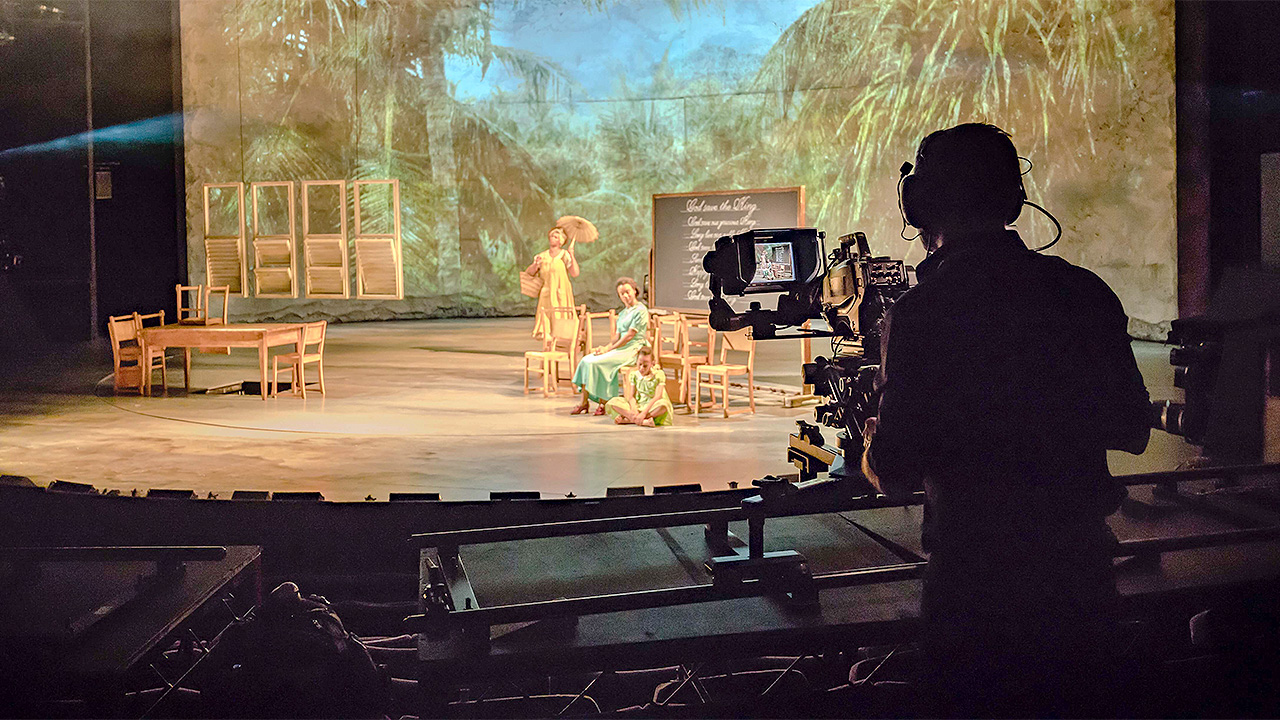

The 2019 production of Romeo and Juliet at Shakespeare’s Globe was made available for free on YouTube between September 2020 and February 2021. Image: Ellie Kurttz / Shakespeare’s Globe

The project surveyed 40 UK performing arts venues (and referenced the report, Culture Restart Toolkit) to better understand the future of digital presentations and why it is being threatened. Despite the alarming findings, Misek is optimistic that theaters’ virtual programming will survive. Some theaters are still planning virtual programs, he notes, though “they just need to get more infrastructure in place and think it through the winter-spring season.”

Ahead of his full report, which will be released in December 2021 and January 2022, here are two key takeaways from Misek’s findings.

Rethinking accessibility strategies

Launched in 2020, Old Vic’s livestreamed series of socially distanced performances, OLD VIC: IN CAMERA, aimed to broaden its accessibility by charing a flat £10 per ticket. Image: Old Vic

Simply livestreaming a performance on Zoom is not an accessibility strategy — it’s doing the bare minimum. If theaters want to meet their viewers’ needs, they need to speak with their audience members.

According to Misek, one surveyed organization reported that the average age of its online audiences mid-70s, many of whom are unable to visit a venue physically. To make sure their audience would engage with their digital programs, the theater surveyed potential visitors in advanced with questions like, “Where would you like to go in the world if you could?” Misek adds, “[If] somebody says, ‘I want to see the Taj Mahal,’ and then [the theater] does a performance creating an imaginative journey for [the audience].”

And because the cost of accessibility tools such as audio descriptions, captions, and sign language interpreters is low, says Misek, theaters can easily build them into their accessibility strategy.

Boosting digital revenue

Despite the ease-of-access that digital shows offer, they don’t guarantee a profit. “Out of 40 organizations I’ve talked to, none have made any profit from going online,” Misek says. “Some almost broke even, but that’s the best they can hope for.”

He notes that in-person events make money off premium seating ticket sales (where a ticket might sell for $200) versus more affordable ticket sales (where a ticket could go for $30). Premium seating sales allow the theater to operate, partially subsidizing general ticket sales. But when a show is aired online, the lack of variable pricing means theaters aren’t able to charge for premium viewing experiences. “Even if you get good numbers, you don’t get that large amount of income,” Misek says.

If theaters decide to retain their virtual presentations, offering specialized or premium digital content could allow them to charge higher prices, enabling them to subsidize affordable or free content.