On April 10, museums around the world celebrated Slow Art Day, a concerted effort to extend the 30-second window the average visitor affords a piece of artwork during any given exhibition walk-through. Institutions typically encourage audiences to look at five objects for ten minutes each on Slow Art Day, a pace designed to unlock the full creative potential of the art on display, but also to address, however temporarily, the accessibility challenges plaguing contemporary curation.

Slow Art activities necessitate increased seating options, for instance, a factor often sorely lacking in cultural heritage spaces, alongside better audio guides, alt text integrations, and heightened docent training. In an interview for the Washington Post, Phil Terry, the founder of Slow Art Day, defined the date’s mission as a way “to make the art experience more inclusive by creating a context where people will include themselves.”

This framing reflects the logic of many museums grappling with notions of inclusivity in a post-COVID landscape; as social justice conversations become a more urgent priority, moves towards equity often sideline a large and important demographic — disabled people. According to the CDC, 26 percent of Americans have a disability, and many more will experience disabling events over the course of their lifetimes, especially as they age. It’s one thing to help museum visitors feel invited into exhibition spaces; it’s quite another to work against the barriers physically keeping them out.

The necessity of accessibility

In an essay for the American Alliance of Museums, Meredith Peruzzi, Director of the National Deaf Life Museum at Gallaudet University, spoke directly on some of the pitfalls of accessibility in a digitally hybrid environment. She cited the lack of captioning for a vast majority of digital events, rendering them inaccessible to those deaf or hard of hearing, and the incompatibility of some virtual content with screen reader software, impeding those who are blind or have low vision. “These are basic, well-known accommodations which should be provided at the outset,” she writes, “yet the burden is still on disabled people to request them, often with great effort.”

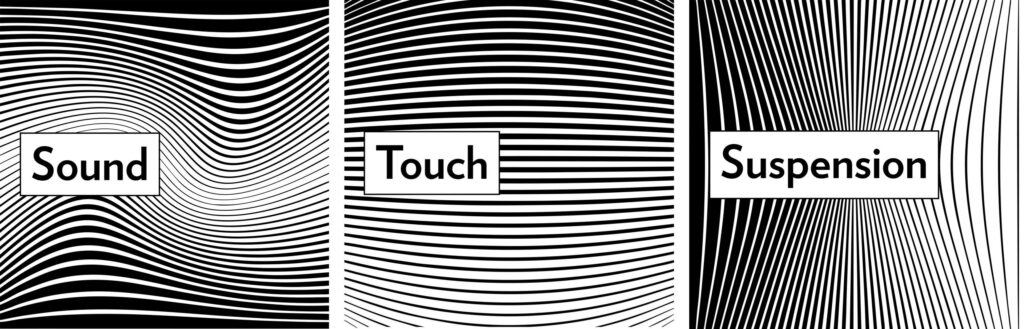

The Guggenheim Museum’s Mind’s Eye audio program offers 10 tracks that each describe a sensory aspect of the museum space, creating an aural and physical experience for blind and low-vision visitors. Images: Audible

Her remarks get straight to the crux of the issue — centering the needs of disabled visitors requires much more than basic ADA compliance. Instead, the process calls upon museum professionals to engage in dialogue with the populations they are trying to reach, and in doing so, radically alter their relationship with tech-based accessibility options. This means keeping abreast of an array of visitor needs — take the Guggenheim’s Mind’s Eye: A Sensory Guide to the Guggenheim New York audio initiative, which may expand experience for partially sighted and low-vision guests, but doesn’t ameliorate mobility challenges experienced by visitors in wheelchairs.

Now that museums across the globe are reopening and funding is beginning to flow again, how can technology assist in increasing accessibility? ARCHES, an EU research initiative dedicated to technological solutions for disabled cultural heritage visitors, has some answers.

Using technology to center visitor needs

In a three-year, multi-museum set of research partnerships, ARCHES, an acronym for Accessible Resources for Cultural Heritage EcoSystems, has been dedicated to technological solutions for disabled museum audiences. The technologies have been co-designed and tested by more than 200 disabled people in Spain, Austria, and the UK, and the results speak for themselves.

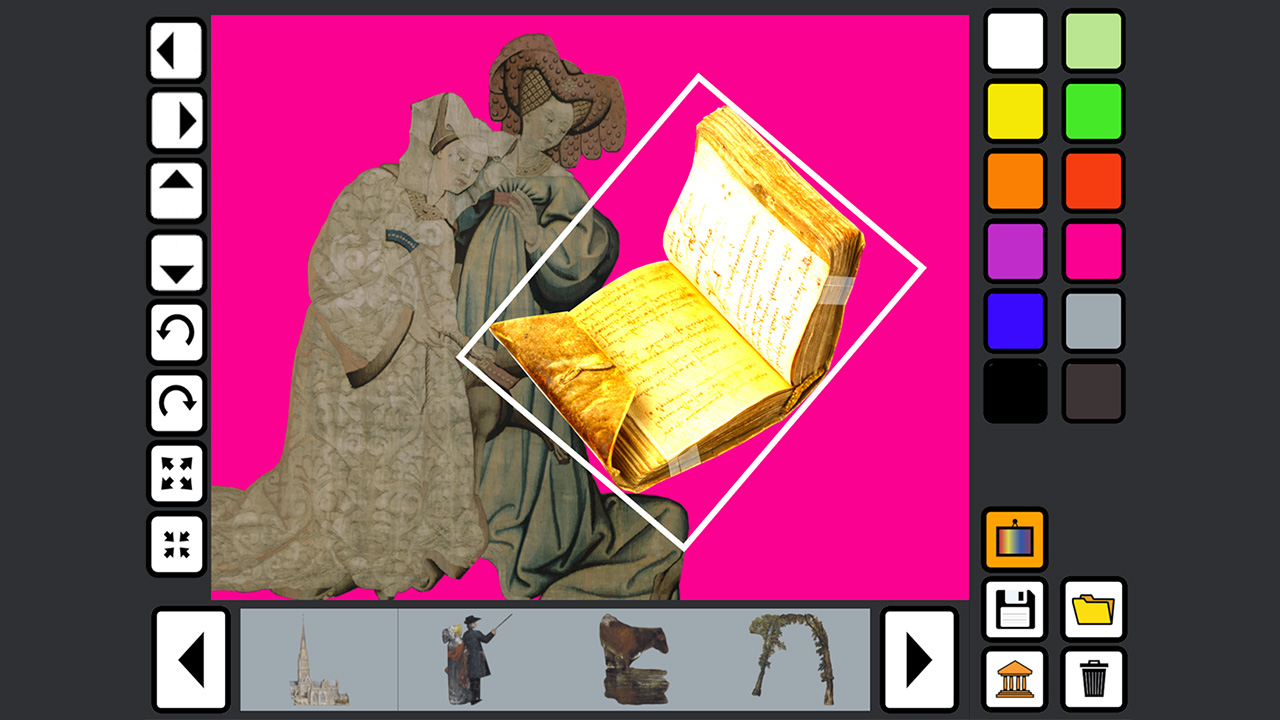

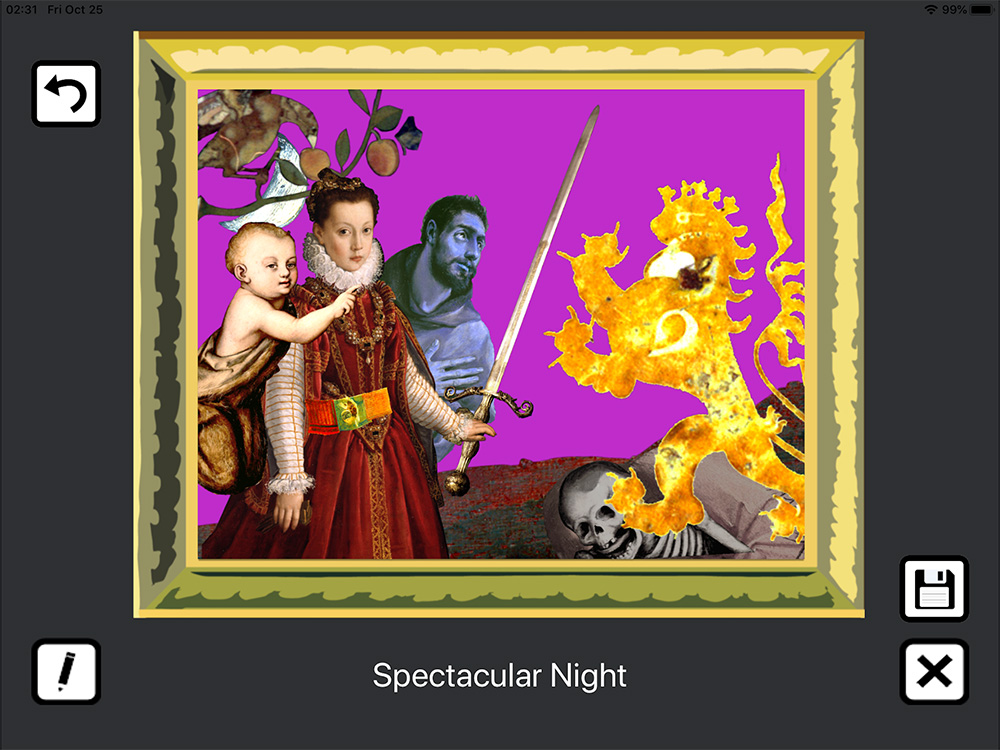

The ARCHES multimedia game, featuring works by partner museums Kunsthistoriches in Vienna, the V&A and Wallace Collection in London, the Museum Thyssen-Bornemisa and Museum Lazaro Galdiano in Madrid, as well as the Museum of Fine Arts in Oviedo, features soundscapes, 3D tactile printing, and sign language in a variety of dialects. In addition to a variety of academic and how-to institutional materials, the initiative is set to present “Please Touch! An inclusive art experience powered by ARCHES” at the 20th edition of the upcoming “Best in Heritage” conference this year.

Above: The ARCHES multimedia game featuring artwork from the Museo Lázaro Galdiano. Below: An interactive tactile relief of Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s “The Nest Robber,” developed by the Kunsthistorisches Museum in association with ARCHES. Images: Google Play, ARCHES

A conversation with its mastermind, Moritz Neumuller, expanded upon ARCHES’ holistic understanding of disability from both the digital and curatorial perspectives. “We can learn so much about how we see art through different sorts of perceptions,” he says. “We organize not around specific disabilities, but around axis preferences. Some of these preferences contradict each other, but we found that it was gratifying and interesting for the people we worked with to discover those who had different needs than themselves. That’s the philosophy of participatory research: listening to these people.”

He also points out nuances in accessibility tech applications that institutions tend to miss. “Many museums have put in great effort to making their permanent collections accessible, but when you go to a museum, you’re really there for something new, like a traveling show. These exhibitions hardly ever have good accessibility features because there is no extra money and no extra time.”

Neumuller makes no bones about the barriers to accessibility in museum tech. “The problem is, small museums without the digital resources in place pre-pandemic had to digitize full-speed. Museums that didn’t have a plan made a digital environment for the mainstream visitors because that’s the first step,” he says.

According to him, the pandemic also “pulled focus” from disability funding and disability-minded curation, resulting in initiatives and partnerships that don’t center the needs of museum audiences’ most vulnerable segments. While apps like Signly, Google Arts & Culture, the “Field For All” Infiniteach extension for neurodivergent visitors, along with heightened XR, EasyRead and instant translation capabilities in smartphones have created occasional, specified opportunities for disability equity, the macro view remains a major technological and philosophical hurdle. “There’s a lot of work to do,” says Neumuller, “but it starts with asking questions and engaging people’s individual agency.”