Ever since NFTs began selling for ungodly millions earlier this year, there’s been a favorite anecdote circulated by the types of people who, pre-COVID, were fond of milling around giant tents looking at art or sitting on chairs listening to experts talking about art. The story goes something like this: back in 2018, Christie’s held its first annual Art+Tech Summit in London where SuperRare, the digital art marketplace, dropped a gift card granting access to a NFT by Robbie Barrat into each attendee’s goodie bag. Two years later, only 12 of 300 unique frames have been claimed. The value of one of Barrat’s “AI Generated Nude Portraits” today? Upwards of $300,000.

The art world establishment, it would seem, is in need of a spot of crypto-education, something Christie’s Education and AndArt Agency’s four-day Zoominar “A Comprehensive Guide to Understanding NFTs (As Taught By the Experts)” was on hand to offer by calling upon crypto artists, art historians, digital art advisors, NFT platform founders, and the like. Here are some of the big questions answered.

How old are NFTs?

Rare Pepe Wallets was the first tool that allowed digital artwork to be bought, sold, traded, and gifted on the blockchain. Image: Rare Pepe Directory

It depends on how generous your definition is. Some might point to Sol LeWitt’s certificates of authenticity for his “Wall Drawings”; most, however, point to the early 2010s and push back on the conventional wisdom that NFTs began with CryptoKitties. Jason Bailey, an early NFT collector and founder of Artnome, traces one of the earliest NFTs back to artist Nili Lerner, who issued 100,000 NILIcoins in 2014, backed by her own art collection in which the artwork is the token. Another important step for the popularization of NFTs was Rare Pepe Wallets, launched in 2016 as the first tool allowing a blockchain community to purchase and sell digital artworks. The following year Cryptopunks, a generative art project that created 10,000 8-bit-style images, went viral.

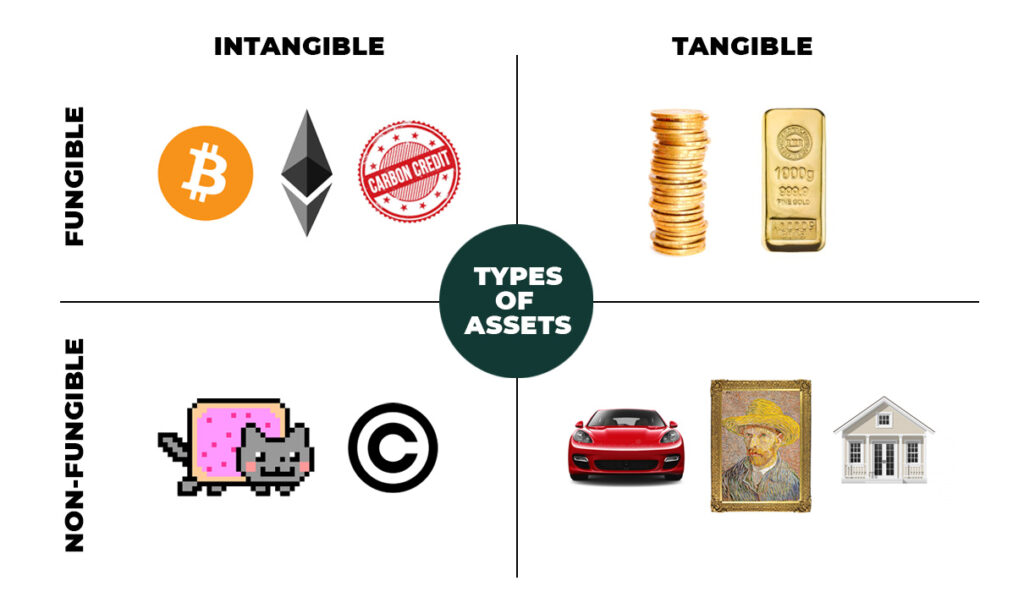

What are you actually buying?

When someone buys an NFT, they don’t acquire the file, but rather a token with a unique number (composed of the contract number and a unique token identifier from within the contract). This token lives on the blockchain. But because files are too big and expensive to feasibly live on the blockchain, the token is linked to the file through a unique cryptographic key called a hash. And where does the hash live? Typically, on the IPFS (InterPlanetary File System), a peer-to-peer network for storing and sharing data.

What are smart contracts and how will they evolve?

Simply put, smart contracts are programs stored on the blockchain that run when predetermined conditions are met, i.e. a buyer matches a seller’s price. Smart contracts have generated great excitement given the ability of artists to ensure a percentage of all future resales, something galleries may also be able to benefit from. At present, most NFT platforms use their own smart contracts, offering uploading artists little scope beyond fixing a royalty percentage, “but they will get a lot more creative in time,” says Fanny Lakoubay a blockchain and art market consultant. “Smart contracts can add any number of details and soon we are going to see platforms upload their own contracts.”

What might NFTs mean for museums?

Crypto Connections by National Museums Liverpool allows visitors to own or co-own museum objects as crypto collectibles. Image: National Museums Liverpool

Bernadine Bröcker Wieder of Vastari, an online art database connecting collectors and curators, offered parallels between key elements of blockchain technology and traditional museum functions: an archived image as a token on a decentralized blockchain; the ticket as a smart contract; the wallet as a collection. Museums, as institutions that prioritize preservation, permanence, and trustworthiness, are well-suited to the emerging the web token economy — as opposed to the preceding information and platform web economies. “In the token economy, we start owning our own assets again,” said Bröcker Wieder. “We have our own contracts and museums can decide where they want their images to go.” The National Museums Liverpool, for example, runs Crypto Connections which invites visitors to choose both a personal possession and a museum piece, before transforming these into crypto-collectibles, digital objects tracked on a blockchain.

How genuine are the environmental concerns surrounding NFTs?

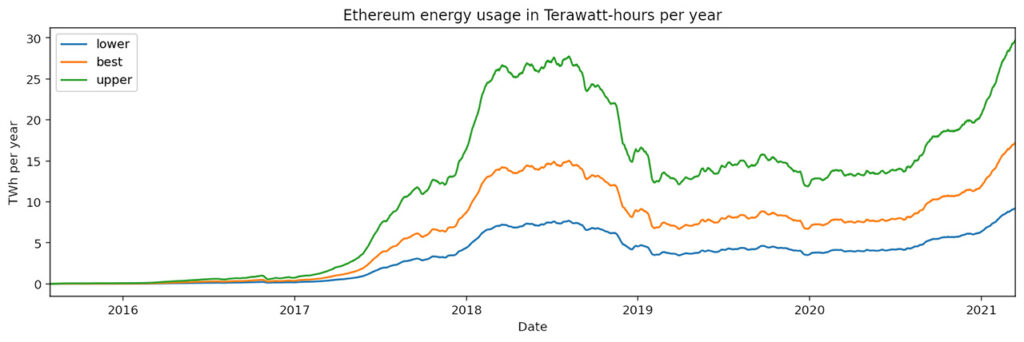

Ethereum’s energy consumption has skyrocketed in 2021 — to almost 30 terawatt-hours of electricity per year, as much as the entire country of Ireland — leading many creators to consider more eco-friendly solutions such as lazy minting. Image: Kyle McDonald

No sooner had NFTs and all the ensuing jargon broken into mainstream consciousness, then the carbon footprint associated with mining cryptocurrency and minting NFTs drew widespread attention (comprehensively laid out here). Most NFTs are minted on the Ethereum blockchain, both inefficient and ecologically costly, with some estimating a single-edition work having the carbon footprint of a one-hour flight. Solutions to such egregious energy consumption include: moving Ethereum from proof-of-work to proof-of-stake protocols (about 100x more energy-efficient), adopting lazy minting whereby NFTs are not minted until purchased, and using bridges and sidechains that connect with more energy-efficient blockchains. Other solutions involve abandoning Ethereum-based NFT platforms altogether and moving to eco-friendly alternatives such as KodaDot and hic et nunc.

What does the future of NFTs look like?

Apple’s latest Mac computers released in late-2020 were notable for introducing the M1 chip, the most powerful processor of its kind. It also points to an emerging ecosystem where the virtual blends seamlessly with the real, particularly once other companies follow suit and integrate such chips into phones and wearables. Though art is the medium through which NFTs are becoming popularized, once broadly understood and accepted, NFTs may well become a common means of owning digital assets — a token granting access to something else from gaming metaverses to secret concerts.

“It’s about authentication,” said Thomas Webb, contemporary artist, hacker, video game developer. “When we arrive in this paradigm, digital assets are no longer owned by the company but by users.”