A modern museum needs 21st century digital infrastructure. This was the frank, and somewhat pointed, assessment of Microsoft’s Catherine Devine in her keynote speech at the DAM and Museums conference — a virtual event that explored digital asset management (DAM) in the context of cultural institutions — on February 10.

Though unsurprising that an individual whose job entails selling digital solutions to global museums and libraries should tout the imperatives of digital transformation, Devine’s focus is not on flashy audience-facing initiatives, but rather on “infrastructure,” systems that institutions can employ to monitor everything from visitor flows to fundraising campaigns to energy consumption.

The past year saw many museums scramble to release digital content for an audience consuming culture primarily through a screen. Devine sees this approach as backward: “The strategy can’t be what is available, what should I use; the strategy should be what am I trying to achieve and what is affordable that allows me to achieve that?”

This requires a mindset shift on the part of museums, an understanding that DAM systems should be focused on more than collections and images — though after a year of working remotely and engaging audiences online, it’s an increasingly pressing realization.

Below are three key insights from the conference participants on building out DAM in museums.

Benefitting storytelling

The USHMM’s DAM system has enriched the telling of Holocaust stories by weaving together multiple perspectives and a mountain of documentation. Image: US Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Marion House

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) holds a vast and fragmented collection of stories. Creating connections between these fragments is key to helping audiences understand the incomprehensible, says Jessica Knight, the museum’s Digital Collections Manager. With 90 million digitized documents, 37,500 hours of witness testimony, and 5600 historic films, USHMM was an early adopter and has made DAM the backbone of its digital strategy (it requires a petabyte of storage, one million gigabytes). “We’re not only making a mountain of Holocaust documentation available,” says Knight, “but allowing researchers and the general public to easily zoom in and zoom out to grasp the expansive scope of the Holocaust.”

Gaining internal institutional support

Gaining organization-wide support for DAM systems is challenging yet key, allowing a centralization of digital assets that benefits various departments. Image: Detroit Institute of Arts

DAM implementation is simple; navigating internal politics less so. This was a common refrain across the event’s panels. Museum resources are tight and all stakeholders need to understand the wide-ranging and long-term value of DAM. Jessica Herczeg-Konecny, the Digital Asset Manager at Detroit Institute of Arts, suggests adopting a marketing mindset. “We call [DAM] the bank and say we are providing users informed decisions,” says Herczeg-Konecny, who likes to refer to the museum’s governance documents, and emphasizes how DAM helps achieve institutional goals by making resources centralized, secure, and accessible.

Another tip to broaden DAM awareness: work across departments. “Integration helps,” says Jennifer Sellar, Digital Assets Manager at the Museum of Modern Art. “You’ll have cheerleaders in other departments and it’s about getting people involved, not making a project for your own department.”

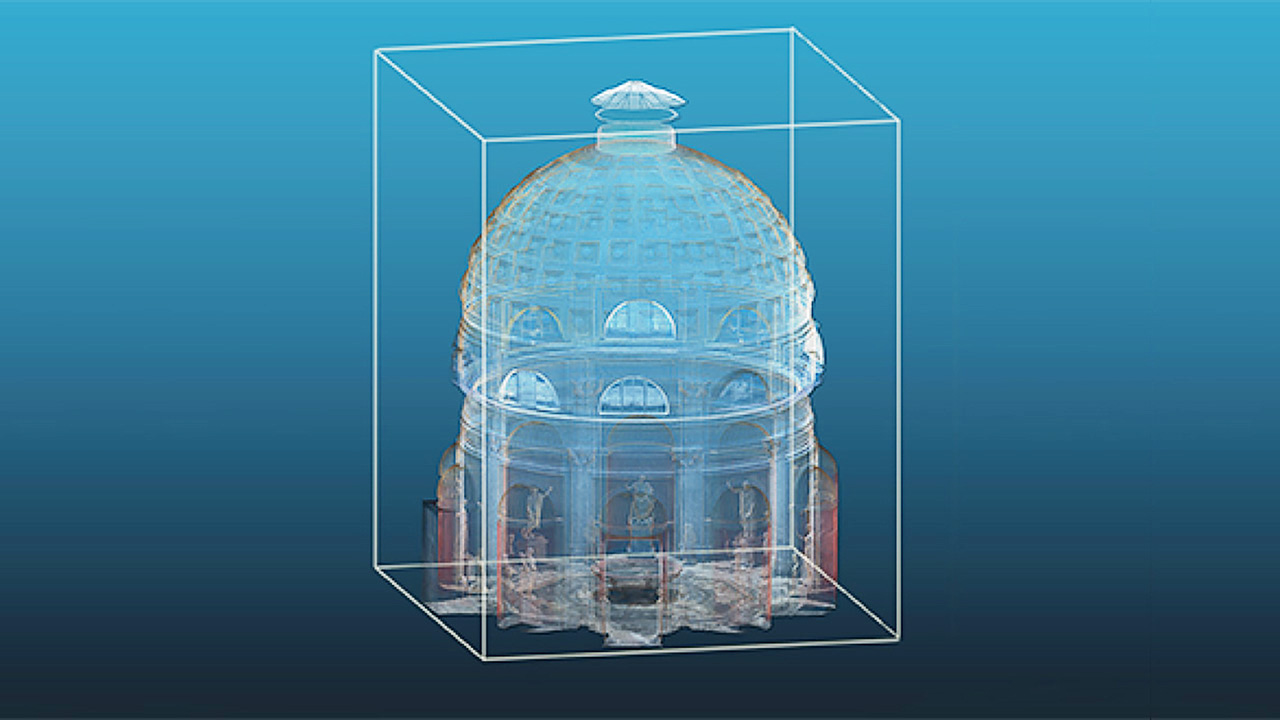

A step-by-step process

Creating a single collection system has been Giovanni Benigni’s “obsession” since arriving at the Vatican Museums. Cataloguing began in the 18th century and starting from 50 different inventories, spread across 16 museums. The sheer array of media made for “a very complex situation,” he says, one exacerbated by “political refusals and more urgent issues such as a digital ticketing system.” In 2017, a long-awaited project to scan glass plates created a broad understanding that a new cataloguing system was necessary. A system was chosen based on storage capacity, ease of management, and cost; and in February, the museums published The Online Catalogue of the Vatican Museums — “a tip of the iceberg,” Benigni says — with additional features to be rolled out step-by-step over time. It’s proof that introducing DAM systems is most often a slow, incremental process.