In 1964, towards the end of his life, Marcel Duchamp delivered the pithiest of artist statements, “Je suis un respirateur.” Too apt that this “respirateur” or “breather” — one who creates art out of everyday life — should be the keeper of a seven-decade oeuvre of abstract paintings and provocative readymades that significantly shifted the plates of Dada, Cubism, and Conceptualism.

So massive was Duchamp’s output that for years, his works, sketches, and papers have been scattered across the collections of various museums. But no more: this week, three institutions have merged their separate Duchamp archives for a digital resource set to illuminate one of the past century’s most seminal artists.

What happened

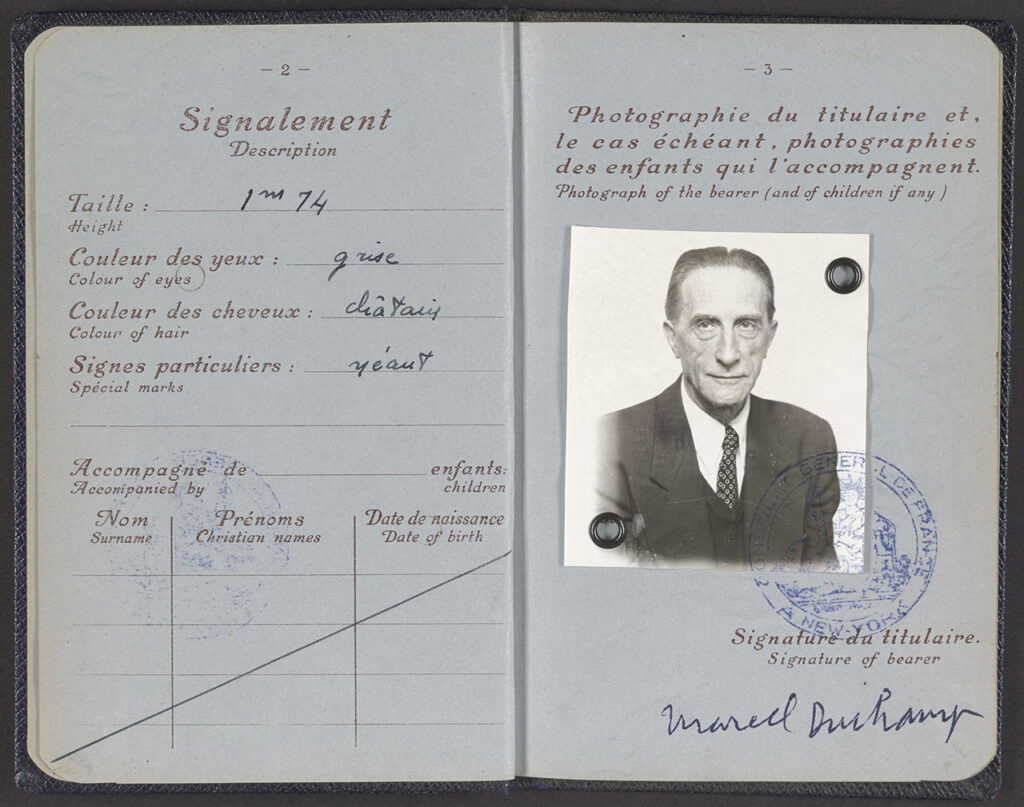

The Duchamp Research Portal houses nearly 50,000 digitized objects covering the artist’s life and work in France and the United States. Image: Marcel Duchamp Republique Française passport, October 22, 1954. Alexina and Marcel Duchamp Papers, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Library and Archives. Gift of Jacqueline, Paul and Peter Matisse in memory of their mother Alexina Duchamp, 1998.

On January 24, the Duchamp Research Portal had its launch, gathering archival documents, correspondence, and contextual images that encompass the entirety of the French artist’s life and work (and of course, his chess fixation). The material, numbering nearly 50,000 digitized images, comprises the Duchamp-related collections of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Association Marcel Duchamp, and Centre Pompidou as part of a seven-year partnership.

Visitors can explore the resource via two major sections. Documents draws from the institutions’ library and archives, notably the Alexina and Marcel Duchamp Papers and Arensberg Archives at the Philadelphia Museum of Art; while Museum Collections features objects from the institutions’ artwork holdings, such as the André Breton and Constantin Brancusi collections at the Centre Pompidou.

All digital images on the Duchamp Research Portal are accompanied by associated metadata, with helpful references to other material in the archive. That means that a search of Man Ray’s portraits of Duchamp, say, will also connect visitors to a trove of related objects not limited to negatives, press articles, and correspondence between the artists.

Why it matters

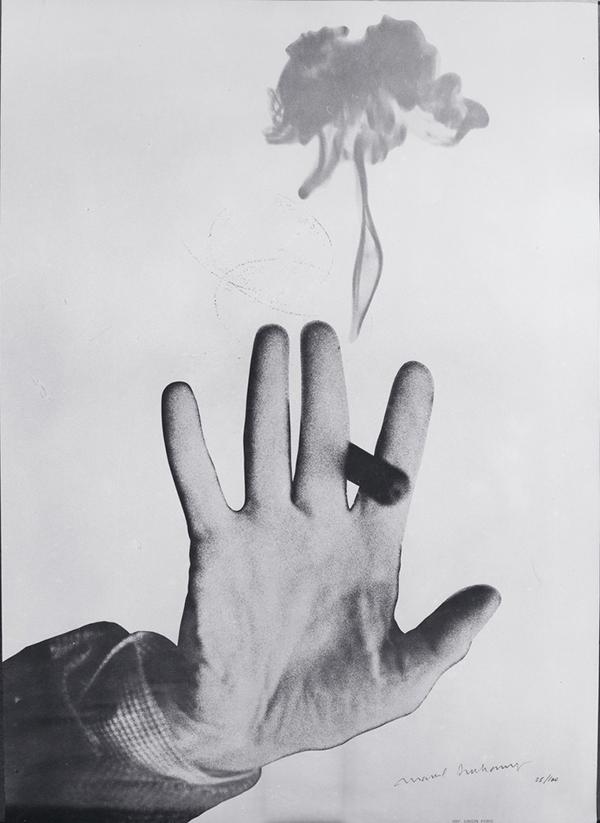

Image: Photograph for Marcel Duchamp exhibition poster at Galerie Givaudan, Paris, 1967. © Centre Pompidou/Mnam-Cci Bibliothèque Kandinsky/Fonds général des photographies.

For Duchamp scholars and art historians, such a resource is an absolute boon, fleshing out not just the artist’s processes, but his connections with the broader avant-garde community. For example, researchers eager for the thinking and development behind Duchamp’s final work, “Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas,” will find 20 years’ worth of detailed notes and technical plans, but also, contributions from fellow artist Paul Matisse and curator Anne d’Harnoncourt.

Naturally, such a repository, heavy with assets from three French and American institutions, has only been made possible by the geography-spanning capabilities offered by digital distribution. And as venues from the Victoria & Albert Museum to the National Museum of African American History and Culture make their digital objects more easily searchable and discoverable, they’re similarly reaching a global (and receptive) audience far exceeding their physical bounds. In this, the digital collection doesn’t just represent a tool, but a potentially key cog in engagement efforts.

What they said

“People are seeking richer online art experiences now more than ever, and this exceptional collaboration with our partners at the Centre Pompidou and the Association Marcel Duchamp, for which we are deeply grateful, offers a wealth of resources.” — Timothy Rub, The George D. Widener Director and CEO, Philadelphia Museum of Art

“Through making these archives accessible globally, we hope that Marcel Duchamp’s idea of freedom will inspire visitors to the site and that they will remember that the artist’s life and art were one, constantly redefining borders of all kinds.” — Antoine Monnier, Director, Association Marcel Duchamp

“No doubt Duchamp, the artist whom Jean Clair called the ‘great fictive one’ (Le grand fictif) would have been pleased to find himself in a virtual world created by friends.” — Xavier Rey, Director of the Musée national d’art moderne, Centre Pompidou