The cultural heritage sector is in flux, and that’s a good thing. As the industry roars back to life post-COVID lockdown, institutions are looking to both sustain and bolster their digital programming, from front-facing viewer engagement schemes to more straightforward collections efforts. Still, the pandemic has cast a long shadow, especially in terms of funding, which means smaller venues often have to fend for themselves when it comes to digital development.

That’s where the Museum Learning Hub comes in, offering free, accessible training to museums that may not have the resources to involve consultants or new hires in their digitization efforts. Their June 2021 broadcast offering, Managing Digitization Projects, was brought to fruition by the Digital Empowerment Project and funding by the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

The four-part workshop consisted of presentations by the brightest minds in museum digitization — from Ann Stegina of the Anchorage Museum in Alaska to Dr. Rhonda D. Jones, a renowned community digital archivist from the University of North Carolina Greensboro. Rounding out the series was June 29’s offering, “Imaging Standards and Logistics in Digitization Projects” with Elizabeth Chiang, the current staff photographer at the George Eastman Museum. In her workshop, Chiang outlined the nuts and bolts of digitization, concentrating on familiarizing viewers with the “vocabulary of museum photography,” and the standards and best practices when it comes to such projects.

Here are the three main takeaways from Chiang’s talk.

Use the resources you already have

While there are definitely perils to using old or subpar equipment, says Chiang, up-cycling where and when you can is a great way to streamline the digitization process. “Digitization in and of itself is not something new,” said Chiang. “Many institutions have been doing this in some manner for decades now. What this means, though, that there is very likely to be legacy equipment that can be repurposed or traded in.” Or, she added, “retrofitted for current-day use.” Chiang also recommends cost-sharing with other small institutions by “banding together to purchase higher end equipment they would not have been able to acquire on their own” and using it on a “rotating schedules.”

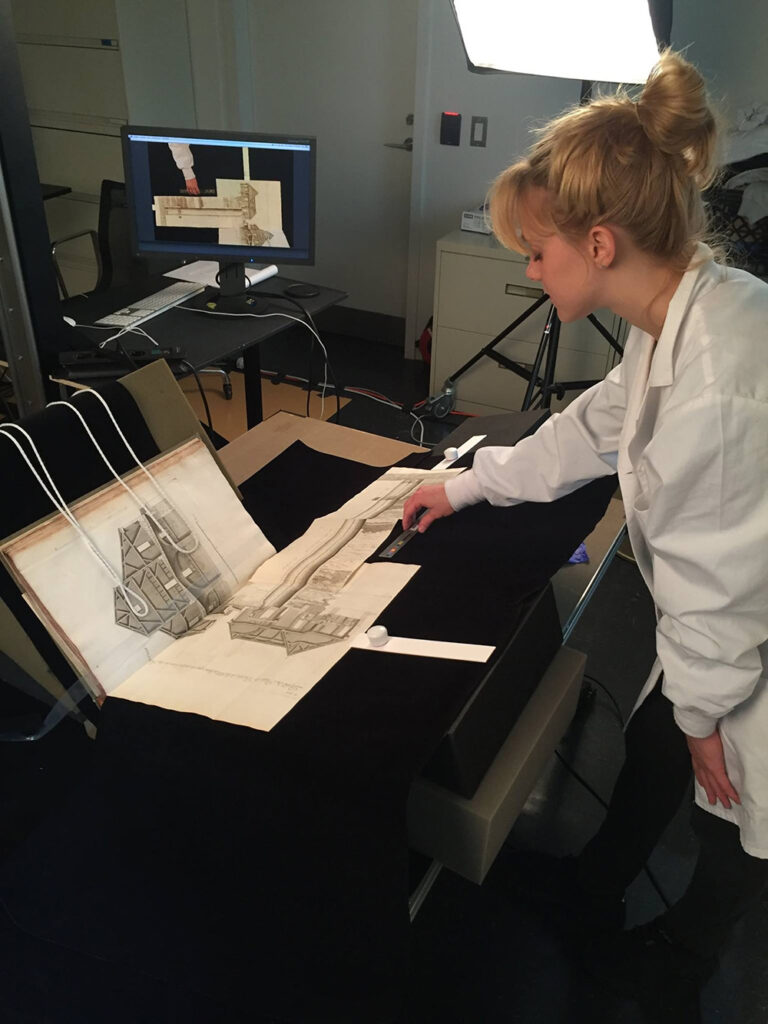

Digitization guidelines, said Chiang, should be weighed alongside other key factors from cost to an institution’s resources. Image: The Smithsonian’s Digitization Program Office

Don’t cut corners on standards

There are aspects you shouldn’t skimp on, however. The biggest one? Storage. “The space needed to store raw files in an under-discussed and sometimes overlooked part of the digitization project,” emphasized Chiang. “The long-term implications of having to redo the work far outweighs the small investment of purchasing additional storage.”

Chiang also underscored the importance of striving towards, if not always adhering to, technical guidelines such as the Federal Archives Digitization Guidelines Initiative (FADGI). “The goal of those standards is provide a baseline for consistency when it comes to image and master file curation,” she said. “They are important because they define trackable and achievable goals for imaging.” While many institutions just embarking on the process won’t hit four-star FADGI standards immediately, Golden Thread and Open DICE are analysis tools that can check master files for compliance. Measuring quality control is particularly important for grant-funded projects; said Chiang, “These are guidelines, not hard and fast rules, and should be taken into consideration alongside other factors such as cost, time, and resources.”

Use discernment to ensure longevity

The long-term viability of digital files is by far the most important aspect of the digitization process, and it’s in this realm that museum workers must weigh best practices with the most pragmatic approach. Said Chiang, “Object handling and understanding the balance between realistic goals and technically perfect images are crucial aspects of digitization.” She suggested consulting the Digital Print Preservation Portal and the Rijksmuseum’s manual for the photography of 3D objects to better understand the individual needs of your institution’s collection — those with mostly flat objects should invest in a scanner, while those with more three-dimensional fare might require an image capture. She also suggested that thinking critically about file types — TIFFs are more widely used, JPEG 2000 is open format — and how they can help a digitization project’s goals.

Finally, Chiang emphasizes the collaborative institutional spirit: “Digitization projects bring together experts from all fields,” she said, “and the corroborative relationships and results are clearly a testament to power across teamwork.”