While in-person culture took a pause in 2020, one city remained a hive of activity in its drive to become a global cultural center. Shenzhen, a concrete and glass embodiment of China’s economic miracle over the past four decades, boasts the world’s second-most skyscrapers, an 11-line metro system, and is the epicenter of the country’s hi-tech industry. With a GDP that trails behind only Shanghai and Beijing, local authorities are now delivering ambitious cultural projects for an increasingly cosmopolitan citizenry.

At present, Shenzhen is the global capital for cultural construction. Last year, it announced 10 large-scale cultural projects worth upward of $2.5 billion. For context, seven of the world’s 13 most expensive projects were located in the southeastern city.

Development is part of Shenzhen’s Double Ten plan to build 10 new cultural districts and regenerate 10 more by 2023. Rather than being concentrated in Shenzhen’s gleaming downtown, projects are spread throughout the city, serving as cultural anchors in newly developed districts.

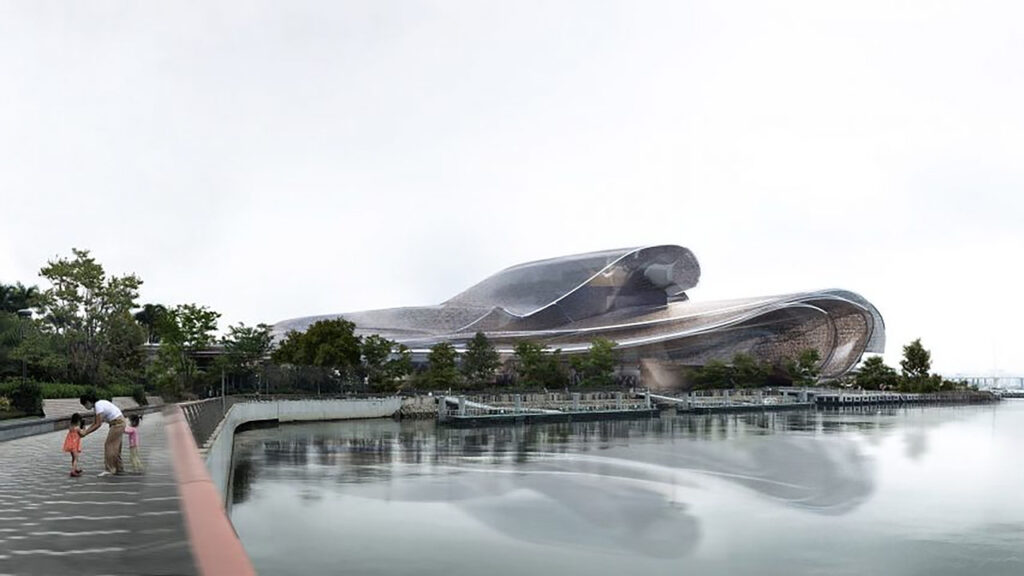

Designed by Ateliers Jean Nouvel, the upcoming Shenzhen Opera House will occupy a site overlooking Shenzhen Bay and integrate into the coastline. Image: Ateliers Jean Nouvel

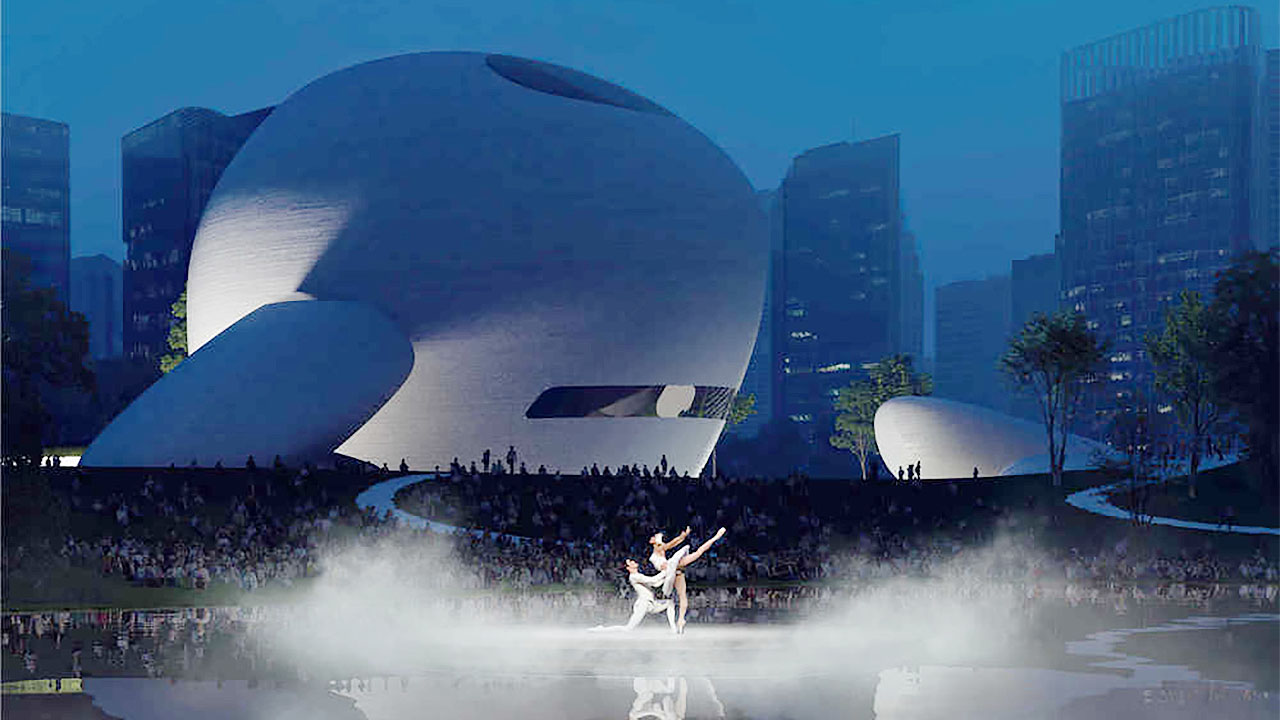

Unsurprisingly, no expense is being spared in realizing this latest stage of the metropolis’ evolution: there’s a Jean Nouvel-designed opera house, a science and technology museum from Zaha Hadid Architects, and a creative design center by MAD Architects, perhaps China’s most celebrated firm.

Museums make up around half of Shenzhen’s new cultural infrastructure projects, a trend echoed across a country that currently opens an average of five museums each week. Seen as a means of amplifying national pride and increasing cultural consumption, authorities openly aspire to turn China into a “museum powerhouse” by 2035.

B+H Architects, 3XN and Zhubo Design’s winning design for the Shenzhen Natural History Museum, set to be the first large-scale museum dedicated to natural history in southern China. Image: artist rendering by 3XN

China’s cultural dynamics are being recalibrated in real time, with Shenzhen and the broader Pearl River Delta emerging as a new hub away from the traditional dominance of Beijing and Shanghai. But what will it take for Shenzhen to establish itself as a truly global cultural attraction? This question was central to Jing Culture & Commerce’s conversation with Shenzhen native, Dr. Heng Zong, a professor focused on culture and creative industries at Lingnan University, Hong Kong.

How would you describe the Pearl River Delta’s cultural development over the past decade?

Overall, the cultural scene in the Pearl River Delta has grown gradually since the 1980s, although there are quite a few asymmetries within the region. Only Guangzhou has a relatively long history in cultural development and by comparison, other cities in the region developed cultural scenes quite recently.

Are there any specific characteristics of the region’s cultural scene?

I think the unique characteristics of the region’s cultural scene lie in its relatively liberal spirit, a kind of chaotic yet organic growth of urban culture. We have a sweeping statement about the difference between north Chinese culture versus south Chinese culture — that is, the north aesthetics emphasizes grandeur, while the south focuses on everyday life. Somehow these characteristics are revealed in cultural practices.

What are the key factors driving the region’s cultural development?

The key factors lie in the opportunity provided by the central government’s decision to use the region as an experimental site for the development of the market economy in the 1980s. Being far away from Beijing, the region was allowed to have some space for transgressive activities. Of course, there were quite a lot of top-town policies in the region too, but autonomous practices were tolerated at that time and this mottled mode of cultural development was very unique.

Due to open in 2023, the Shenzhen Science and Technology Museum has been designed by Zaha Hadid Architects to be a landmark stop in the Guangzhou-Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation Corridor. Image: Zaha Hadid Architects

What are the fundamental differences between Shenzhen’s culture sector and those in Beijing and Shanghai?

Compared with Beijing and Shanghai, where grassroots cultural practices historically have the soil to grow in, the cultural sector in Shenzhen emerged a decade later and depends on top-down planning. For instance, the most well-known arts infrastructures and events in the city are OCT LOFT, He Xiangning Art Museum, and Shenzhen Biennale of Urbanism/Architecture. These are all governmental projects, with some led by state-owned enterprises.

Are there any specific advantages to this top-down planning?

Top-down planning has merits in that it can construct a cultural sector in a short time and can allocate many resources efficiently. For instance, scholars argue the success of the OCT LOFT project derives from the authorities’ push to develop Shenzhen into a design hub. Shenzhen is a very rare case to have prioritize one sector of the creative industries, design.

Long-term, do you see Shenzhen’s cultural identity centered on design?

Shenzhen officials have the ambition to develop its design industry. The city was appointed as a UNESCO City of Design in November 2008, OCT LOFT is dedicated to design, and the Design Society, opened in collaboration with the V&A, seems to demonstrate that the government’s strategy is working.