Decades upon decades of museum exhibits have cemented a view of ancient Greek and Roman statuary in unmistakably white marble — pristine and colorless surfaces that, coupled with formal proportions, have captured what has come to be accepted as the classical ideal. But the craftsmen of antiquity never thought of their gods and subjects as this wan and pale. Rather, as a growing body of modern-day scholarship has emphasized, these sculptures were vibrantly ornamented and colored with pigmentation.

In the past two decades, polychromy has caught on in museums, with projects like the ongoing touring exhibition Gods in Color and Getty Villa’s The Color of Life deploying richly multicolored reconstructions to spotlight how ancient artisans sought mimesis through form and color. Slowly and steadily, they’ve injected a much-needed corrective to the perception of an achromatic antiquity. Now, the Metropolitan Museum of Art is next to step up with its own showcase that recenters its Greek and Roman galleries in color.

What happened

Running until March 2023, Chroma dots the Met’s Greek and Roman galleries with full-sized, full-color reconstructions, most on loan from the Liebieghaus Sculpture Collection. Image: Min Chen

Yesterday, the Met opened Chroma, an exhibition that’s spread across its Greek and Roman galleries. Until March 2023, the institution’s sea of white marble monuments will be dotted throughout with vividly tinted reconstructions — a cuirassed torso, a funerary statue, the Alexander sarcophagus — most on loan from the Liebieghaus Sculpture Collection in Frankfurt, Germany. They were developed by classical archaeologists Vinzenz Brinkmann, who heads up the Department of Antiquity at Liebieghaus, and Ulrike Koch-Brinkmann, using a range of analytical techniques and four decades’ worth of archaeological research.

To identify original surface treatments on surviving sculptures, processes not limited to 3D imagining, spectroscopy, and ultraviolet luminescence were deployed. The recreations were then 3D-printed in polymethyl methacrylate and augmented with marble stucco, before being intricately painted with natural pigments and/or gold foil. “This approximation is very close to what it looked like in antiquity,” noted Vinzenz Brinkmann at the exhibition’s preview. “It is color and ornamentation [drawn from] a high scholarly level.”

The painted replica of the Sphinx finial was specially produced for the Met’s exhibition and is installed alongside the original statues in the museum’s collection. Image: Min Chen

Chroma AR invites users to engage with the field of polychromy. Image: Chroma AR

At the heart of Chroma is a reconstruction of an Archaic period Sphinx finial, produced especially for the Met’s show, and recreated with a coat of resplendent azurite, cinnabar, and gilded copper. It’s installed alongside the original statue, part of the museum’s holdings. Additionally, a special gallery arraying 22 other works of art — from ancient Mediterranean sculptures to ancient Greek terracotta vases — is included in Chroma’s journey to further draw out the field and history of polychromy.

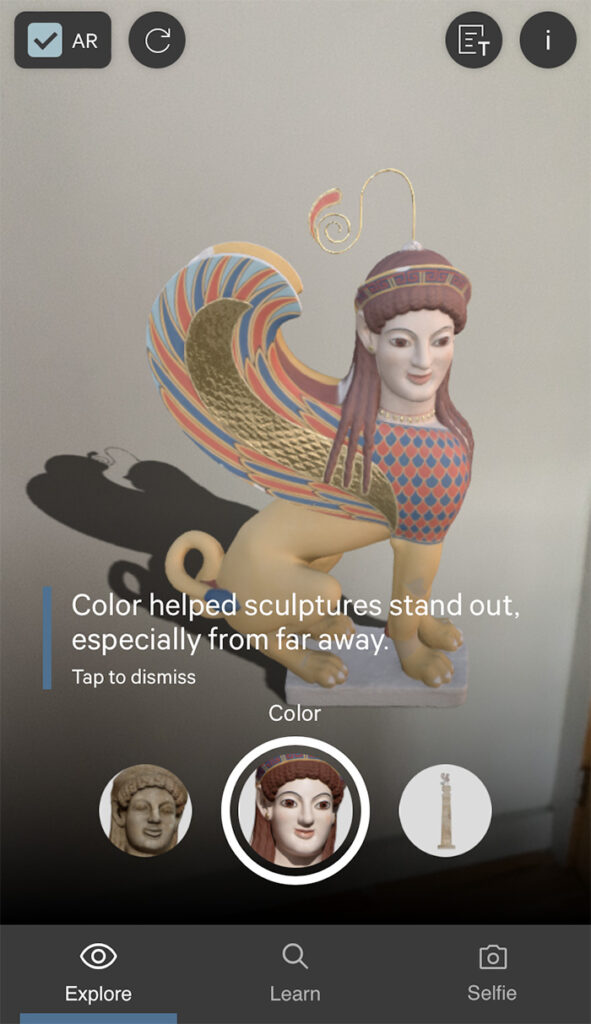

The exhibition comes further accompanied by Chroma AR, a mobile experience created in partnership with Bluecadet. Available throughout the exhibition’s run, the platform allows users to “place” the aforementioned Sphinx amid their particular environs, viewing it in white or in full-color using Niantic’s AR technology. Additional features include a selfie-friendly filter, and a scavenger hunt that imparts the history behind the Sphinx and the science behind its reconstruction.

Why it matters

“This approximation is very close to what it looked like in antiquity,” noted Vinzenz Brinkmann at the exhibition’s preview. Image: Min Chen

To recast Greek and Roman antiquity in living color, as their artisans intended, Brinkmann and the Met team have leveraged a central tool: reconstructions. While these casts may have fallen out of fashion in most museums, often in favor of original works, they represent a vital instrument with which to convey historical accuracy. It’s the kind of fidelity that an actual ancient sculpture, chipped and weathered as it’s likely to be, might fail to capture.

With the advent of digital imaging and 3D printing, these replicas, too, have become easy to produce, making them accessible and useful educational tools for museums. And as the Institute for Digital Archaeology has proposed, they might also play roles in furthering cultural restitutions, wherein reconstructions may take the place of originals in museum displays, enabling the latter to be repatriated without diminishing an institution’s storytelling.

What they said

“This innovative exhibition will activate the Met’s displays of ancient Greek and Roman art like never before by displaying colorful reconstructions of ancient sculptures throughout the galleries. It is truly an exhibition that brings history to life through rigorous research and scientific investigation, and presents new information about works that have long been in The Met collection.” — Max Hollein, Marina Kellen French Director, the Metropolitan Museum of Art