As China’s wenchuang trend — wherein cultural products have spurred a multimillion-dollar IP industry, covered in our recent report — has cultivated the appeal of and demand for cultural relics, Chinese institutions have found myriad ways to package and sell the country’s cultural heritage. From blind-boxed figurines to replicas to popsicles, these physical products have spurred a marketplace that, at Tmall’s 2021 Double 11 Festival, saw sales growing by 400 percent year-on-year.

Lately (and quite naturally), these cultural artifacts have found themselves licensed in new digital, tech-enabled iterations. The past year has logged the launch of virtual blind boxes by Henan Museum, an AR trading card game by Dunhuang Culture & Tourism Group, and digital collectibles released by Alipay in partnership with 24 Chinese museums, in addition to Palace Museum’s December exhibition that featured AR and VR-enabled renderings of “digital cultural relics.”

China’s digital heritage has risen alongside the growth in online programming over pandemic lockdowns, but also, the desire to attract younger consumers increasingly inclined to digital goods such as NFTs. As Chinese cities including Shanghai currently undergo another round of quarantine, such digital cultural relics continue to resonate, not just for cultural consumers, but for Chinese institutions hoping to leverage their cultural IP across formats. Here’s a round-up of three recent projects that have merged cultural relics with tech-forward approaches.

Ningxia Museum’s “360 Pictorial” screensavers

Ningxia Museum’s “360 Pictorial” screensaver has been downloaded more than 350 million times. Image: Ningxia Museum on WeChat

Last month, Ningxia Museum collaborated with Zhongchuan Cultural Protection to release its “360 Pictorial” (360画报) screensaver. The digital download features 26 cultural artifacts from the museum’s collection, including a gilt bronze bull and a stone carving of the Hu Xuanwu tomb gate. The images of these cultural treasures previously appeared on the 2022 Cultural and Creative National Treasure Calendar, highlighting relics from 11 other institutions including the Sichuan Museum and Shanxi Museum.

Happening alongside the release of Ningxia Museum’s screensaver were Weibo activations, “Good Morning, National Treasure Calendar” (早安,国宝日历) and “Follow The Pictorial To View Cultural Relics” (跟着画报看文物), topics that encouraged audience participation. Since its launch, the screensaver has been downloaded more than 350 million times, bringing the institution’s cultural relics into the homes and offices of consumers.

Shanxi Museum in VR

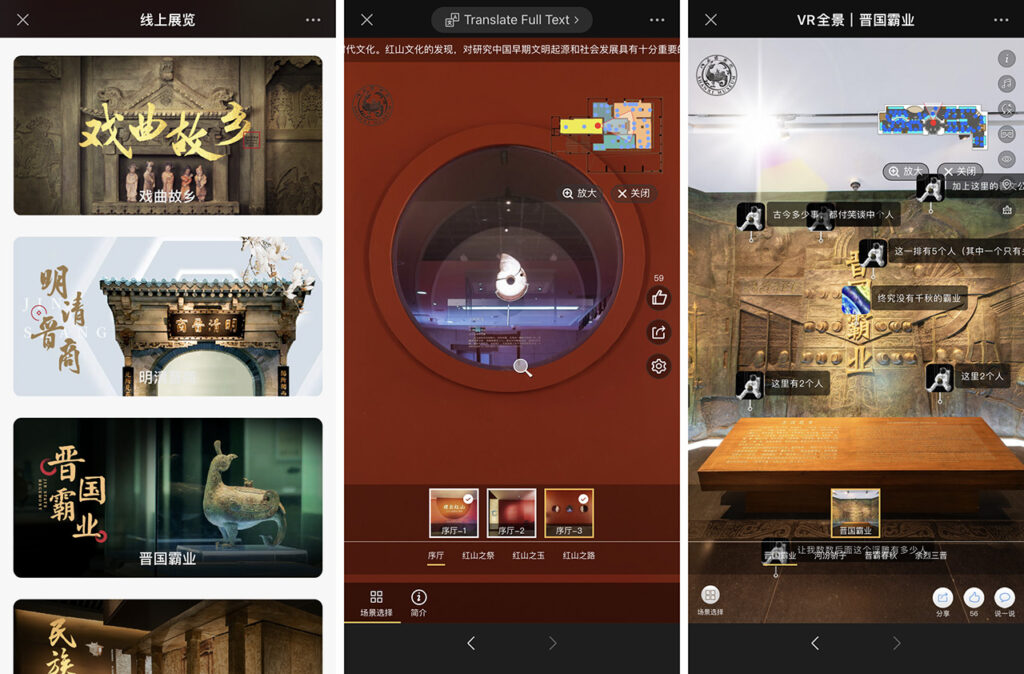

Shanxi Museum’s VR exhibition tours enable users to zoom into various relics for further detail and leave comments. Image: Shanxi Museum on WeChat

In a boon for residents in lockdown (or living abroad), the Shanxi Museum has brought 22 of its physical exhibitions online. Via the venue’s official WeChat account, users can access exhibitions including Silk Road Cultural Relics, Hongshan Cultural Relics, and the Art of Shanxi Liuli.

Each interactive exhibition enables 360-degree panoramic views, which can be scrolled through by using arrows or as an immersive VR experience. In displays throughout the digital exhibitions, users can zoom in for further details and are encouraged to leave comments.

Ice Skating in the Forbidden City

The Palace Museum’s first NFT collection includes a gamified element, encouraging buyers to purchase and combine a number of digital collectibles to synthesize a bigger animation. Image: TheOne.Art on WeChat

In February, coinciding and in collaboration with the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing, Palace Museum released a series of digital collectibles, entitled Ice Skating in the Forbidden City, featuring animations of the ancient work, “Ice Play” (冰嬉图). While such animated paintings have grown in popularity among Chinese institutions — notably by Suning Art Museum as a way to enrich visitor engagement — this project further invited audiences to purchase these digital scrolls. The series was sold in 35,000 virtual blind boxes, divided into eight editions, each showing different sections of the artwork. In a gamified element, buyers could collect a number of digital images of the same style to synthesize a bigger animation.

As one of the earliest institutions to enter and maximize the licensing space, Palace Museum’s gathering push into the digital realm doesn’t just highlight the possibilities of virtualizing cultural relics — in turn offering audiences an education in Chinese cultural heritage — but also, the potential for these digital offerings to generate revenue.